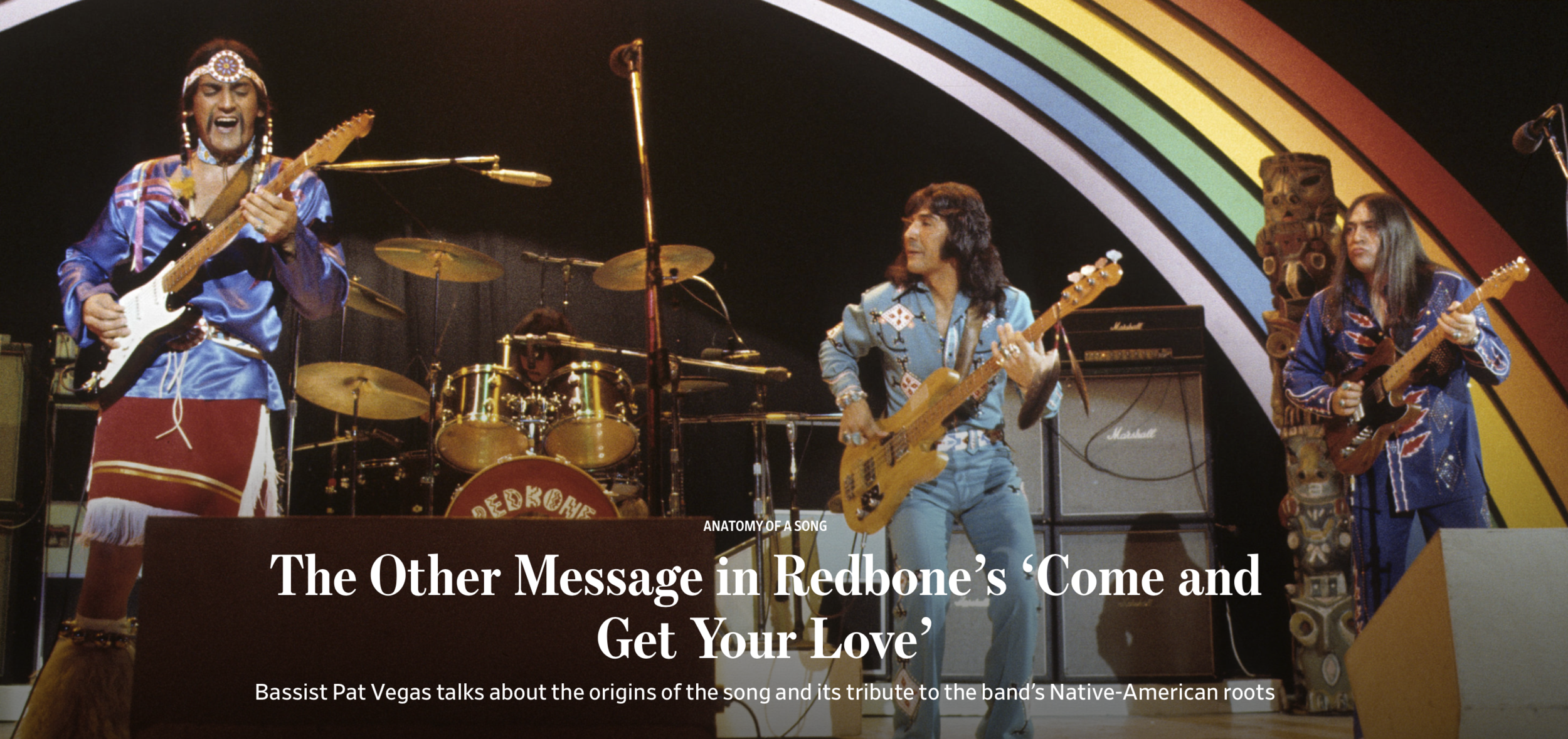

Tony Bellamy, Pat Vegas and Lolly Vegas performing in March 1974, the year ‘Come and Get Your Love’ hit No. 5 on the Billboard pop chart. WALT DISNEY TELEVISION/GETTY IMAGES

Reprinted from the Wall Street Journal. Read the original article here.

By Marc Myers

Jan. 21, 2020 10:24 am ET

Formed in 1969, Redbone was one of the first Native-American rock bands in the album era. A chunky tribal dance beat helped propel their single “Come and Get Your Love” to No. 5 on the Billboard pop chart in 1974.

The song has been used often in films and covered numerous times, including a version by Real McCoy that reached No. 19 on the Billboard pop chart and No. 1 on the dance chart in 1995.

Recently, Pat Vegas, Redbone’s bassist and the song’s arranger and co-producer, looked back at the hit’s evolution and his contribution. His brother, Lolly, the song’s writer, died in 2010. Edited from an interview.

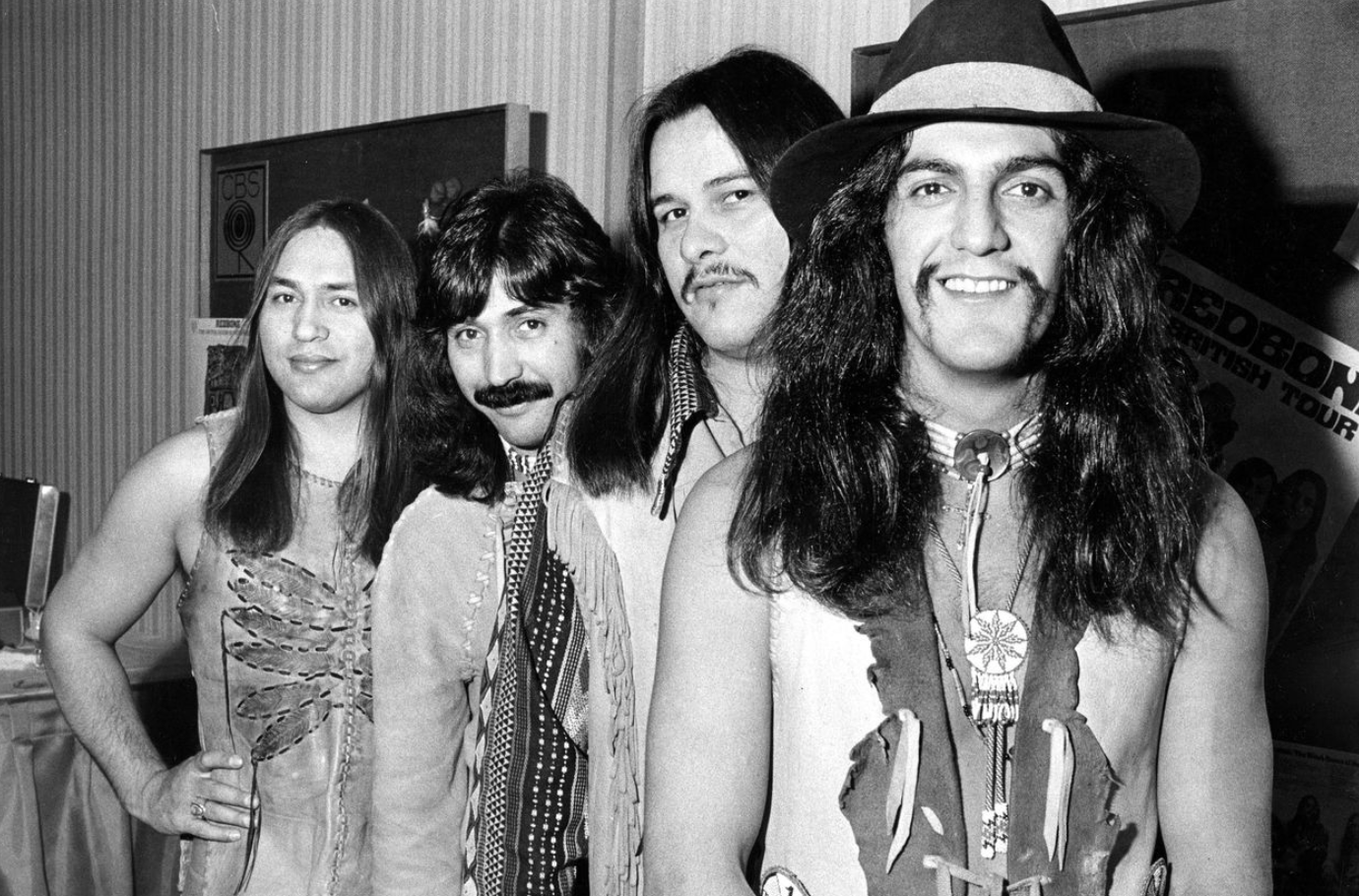

Redbone in 1971: left to right, Lolly Vegas, Pat Vegas, Pete DePoe and Tony Bellamy. PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK

Pat Vegas: My father and mother met during the Depression in Texas and moved onto an Indian reservation in Arizona. When I was a year old in 1942, we moved with my older brother, Lolly, to Fresno, Calif., where my father found a job working in the Coalinga Oil Field.

Our family name was Vasquez. We were descendants of Native-American tribes of the Southwest and proud of our heritage. My mother’s father, Antonio Beltrán, was a musician. So was everyone in his family. His sister was Lola Beltrán, Mexico’s most famous ranchera singer and a favorite of Linda Ronstadt.

My grandfather had a guitar he played all the time at family gatherings. He kept it on top of his armoire. He said, “When you can reach that guitar, it’s yours.” A few days later, when I was 5, I stood on a chair, took down the guitar and started practicing.

My brother already was playing guitar. He played it like a piano, picking at the strings with all four fingers at once. We formed our first local band when I was 14, playing Top-40 hits. Soon I had to switch to bass. We couldn’t find a bass player who could keep up with our unusual rhythms.

By then, my parents had divorced. When my mom remarried, we added my step-father’s last name to ours—Vasquez-Vega. In the early 1960s, Lolly and I formed the Avantis, a surf-rock band, and looked for work at clubs on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles.

But many club owners told us they didn’t hire Chicanos, Indians or blacks for their house bands. At Gazzarri’s, the owner, Bill Gazzarri, liked us. He added an “s” to our last name, and we performed there as Pat & Lolly Vegas.

As our reputations grew, we worked as songwriters, arrangers and studio musicians in Hollywood and Las Vegas. We played on records by Sonny & Cher, James Brown, Tina Turner and others.

We also released singles and an album for Mercury in ’66—”Pat & Lolly Vegas: At the Haunted House.” The Haunted House was an L.A. discotheque.

In 1969, Lolly and I decided to form a rock band that embraced our Native-American heritage. We needed a name.

My grandfather was from Texarkana, Texas, and had played guitar in a five-piece Cajun band on the weekends right over the Louisiana border. When I was little, he told me about the tribes uniting to fight and defeat General Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Afterward, he said, our people were on the run and went first to Canada and intermingled with the Acadians. Then they relocated to southwestern Louisiana, where many Cajuns lived. Lolly and I chose Redbone to pay tribute to our people for their courage and bravery.

One night, in 1973, Lolly called me at around 3 a.m. He asked me to come over. He had an idea for a song and wanted help. I grabbed my bass and tape recorder and went over to his house in Hollywood.

Lolly played me what he had—a few plain chords, from C to D to B to E to A. It was a little sing-songy and needed an arrangement. We also had to change some of the lyrics. They needed to be smarter.

I told him to leave me alone in the room with it. The first thing I did was come up with the bass line. It immediately turned the song around. Then I altered the chord voicings and gave them a rhythmic feel.

As I worked on the song and the arrangement, I thought about how Native Americans were always depicted in Westerns as bad guys being chased by the cavalry. I wanted the song to change that image.

My brother had called the song “I Want to Give You My Love.” I changed it to “Come and Get Your Love.” We wanted to show that our people were about love, not about massacring.

By then, I had been in the room for hours putting the song together, getting the right rhythm and taping the music on my recorder. When the demo was perfect, I played Lolly the tape. He loved it.

We also worked on the words. We opened the first verse with the word “hail,” like glory to the world:

“Hail / What’s the matter with your hair, yeah-yeah / Hail / What’s the matter with your mind / and your sign and-ah oh-oh-ohhh.”

The song’s verses refer to the excuses people back then came up with to explain why they were feeling out of sorts. Worrying about your state of mind, your astrological sign, your hair—they all got in the way of natural, honest feelings:

“Hail / Nothing the matter with your head, baby / Find it, come on and find it / Hail / With-it baby, ‘cause you’re fine and you’re mine / and you look so divine.”

The chorus—“Come and get your love”—is about pure love, without all the overthinking and trendy phrases.

Many think the song is just about a man singing to a woman. It is, but it’s also about the coming together of different peoples.

The following day, Lolly and I went into Devonshire Sound Studios in L.A. with Tony Bellamy, our guitarist, and Pete DePoe on drums. Butch Rillera, who would become our next drummer, overdubbed background vocals.

The beat was a joint effort, with Pete laying it down while we fine-tuned it. What we came up with was a Native-American dance beat. When you dance to the Indian tom-tom, it’s a straight beat with an emphasis on the upbeat—don don-don, don don-don. Not don-don don-don, like in the movies.

On the recording, after the opening drum beat, my Fender Precision bass line mirrored Pete’s tom-tom dance beat. If you listen carefully, the bass line drives the song.

Lolly played an electrified sitar that Bob Bogle and Don Wilson of the Ventures had given me at a party as a gift. They were good friends.

At the end of the chorus—”Come and get your love”—Lolly switched to his Fender Telecaster and played a wailing bluesy line.

We also wanted strings for drama. So Lolly and I got together with arranger Gene Page and told him where the strings should and shouldn’t play. We used four strings and doubled them—meaning they recorded their part twice for a fuller sound.

The song was on our fifth album, “Wovoka.” When the album came out in late ’73, I brought it over to my mom’s house in Salinas. As soon as “Come and Get Your Love” came on, she got up and started doing a tribal dance. She heard the beat and was so proud.

When the song reached No. 5 in April ’74, I was thrilled. People were finally getting to know what we could do. We had proved that a Native-American band could sing about love and have a pop hit on its own terms.

We toured that year and played the song on TV’s “Midnight Special” and “In Concert.” Tony dressed in a traditional Native-American costume, with a bustle of eagle feathers on his back. He opened the song with a tribal dance.

On the road, when we’d first come out on stage in traditional outfits, people in the front rows freaked and backed up about four feet. It was funny. They’d seen too many Westerns.